Confinement

Comprehensive accounting for atmospheric mass and energy is a distinctive feature of ExpCGM, designed to account for the cumulative input of feedback energy over cosmic time. An excess of heating over radiative cooling pushes some of the atmosphere’s baryons beyond the halo’s virial radius $(R_{\rm halo})$, but those baryons are not necessarily unbound.

This page explains how ExpCGM models gravitational confinement of a galaxy’s atmosphere and discusses how the baseline model presented on the Essentials page can be extended to account for gravitating matter that has not yet fallen into the halo. Its first section outlines the relationship between gravitational confinement and a pressure profile’s shape function, using the NFW gravitational potential as an example. The next section explains why atmospheric gas pushed beyond $R_{\rm halo}$ in the real universe is rarely completely unbound, because of the additional mass outside of $R_{\rm halo}$. The concluding section extends the basic model for gravitational confinement to include mass beyond $R_{\rm halo}$ and relates that additional mass to the halo’s mass accretion rate. That addition to the halo’s potential well changes the relationships between an atmosphere’s mean specific energy $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$, its equilibrium radius $r_{\rm CGM}$, and its pressure normalization $P_{\rm CGM}$. The changes are typically greatest at early times, while the halo’s accretion rate is especially large.

Contents

Binding Energy

An atmosphere’s binding energy depends on how its support energy compares with the depth of the potential well confining it. According to the ExpCGM framework, the specific support energy of a gas layer at radius $r$ is \(\frac {3} {2} \frac {P} {f_{\rm th} \rho} = \left( \frac {3 f_\varphi} {2 \alpha_{\rm eff}} \right) v_{\rm c}^2 (r)\) when a combination of thermal and turbulent energy supports a steady-state galactic atmosphere. (See the Essentials page for an explanation and definitions of the symbols.) The specific gravitational binding energy of that gas layer is \(\varepsilon_{\rm bind} (r) = \left( \frac {3 f_\varphi} {2 \alpha_{\rm eff}} \right) v_{\rm c}^2 (r) + \varphi(r) - \varphi_\infty\) in which $\varphi(r)$ is the gravitational potential and $\varphi_\infty$ is its limit as $r \rightarrow \infty$. A gas layer satifying the condition \(\alpha_{\rm eff}(r) > \frac {3 f_\varphi} {2} \frac {v_{\rm c}^2(r)} {\varphi_\infty - \varphi(r)}\) has $\varepsilon_{\rm bind} < 0$ and is therefore bound by the potential well. Otherwise, pressure applied by overlying atmospheric layers needs to confine the layer at radius $r$.

An NFW Example

To see how gravity and external pressure jointly confine atmospheric gas in the ExpCGM framework, consider an NFW potential well \(\varphi_{\rm NFW} (x) = A_{\rm NFW} v_\varphi^2 \left[ 1 - \frac {\ln (1 + x)} {x} \right]\) in which $x = r / r_{\rm s}$ expresses radius in units of the potential’s scale radius $r_{\rm s}$ and $A_{\rm NFW} = 4.625$ is a normalization factor. The parameter $v_\varphi$ is then the maximum value attained by the potential’s circular velocity profile \(v_{\rm c}^2 (x) = A_{\rm NFW} v_\varphi^2 \left[ \frac {\ln (1 + x)} {x} - \frac {1} {1 + x} \right]\) which reaches $v_\varphi^2$ at $r_{\rm max} = 2.163 r_{\rm s}$. Circular velocity is nearly constant with radius near that peak but gradually declines at $r > r_{\rm max}$. Because of that decline, the value of $\varphi_\infty$ is finite. The condition for purely gravitational confinement of a gas layer in an NFW potential well therefore reduces to \(\alpha_{\rm eff} > \frac {3} {2} \left[ 1 - \frac {x} { (1 + x) \ln (1 + x) } \right]\) Layers with smaller values of $\alpha_{\rm eff}$ need to be confined by overlying layers, meaning that the outermost layers of a gravitationally confined atmosphere need to have $\alpha_{\rm eff} > 3/2$ in order to remain bound without external pressure confinement.

Critical Confinement

More generally, $\alpha_{\rm eff} = 3/2$ is a critical value for gravitational confinement of atmospheres in which the ratio of support energy density to total pressure is 3/2, for the following reasons:

-

All layers having $\alpha_{\rm eff} > 3/2$ are gravitationally bound, because each layer’s specific support energy $3 v_{\rm c}^2(r) / 2 \alpha_{\rm eff} (r)$ is less than the specific energy $v_{\rm c}^2(r) = G M_r / r$ required to escape the gravitational attraction of the total mass $M_r$ within $r$. (This general result does not depend on the details of $\varphi$.)

-

Gravitational confinement at small radii ($r \ll r_{\rm s}$) does not depend on $\alpha_{\rm eff}$ in potential wells with $v_{\rm c}^2 \ll \varphi_\infty$ at small radii. (This result applies to potential wells in which $v_c^2$ goes to zero as $r \rightarrow 0$, as in the NFW potential.)

-

Atmospheric layers that have $\alpha_{\rm eff} < 3/2$ can be pressure confined by the weight of overlying layers, but the pressure profile must steepen to $\alpha_{\rm eff} > 3/2$ at larger radii in order for the entire atmosphere to be gravitationally confined.

-

Outer atmospheric layers with $\alpha_{\rm eff} < 3/2$ need to be confined by external pressure forces.

If the radial gradient of the thermal support fraction $f_{\rm th}$ is insignificant, then $\alpha$ replaces $\alpha_{\rm eff}$ in this bullet list.

The atmospheres of galaxy clusters appear to abide by the constraints listed above, since observations of their thermal pressure profiles show that $\alpha \lesssim 1$ at $r \ll r_{\rm s}$ and $\alpha > 2$ at $r \gg r_{\rm s}$ (e.g., Pointecouteau et al. 2021, A&A, 651, A73).

Technically, all ExpCGM model atmospheres are partially confined by external pressure because $P(r_{\rm CGM})$ is non-zero. However, the effects of external pressure confinement on atmospheric structure at smaller radii are negligible for atmospheres with $\alpha > 3/2$ in the vicinity of $r_{\rm CGM}$.

Marginal Binding

In the ExpCGM framework, boosting an atmosphere’s mean specific energy restricts the set of pressure profiles that can be in a static equilibrium configuration. For example, the maximum value of mean specific energy in an atmosphere with $\alpha_{\rm eff} > 3/2$ cannot exceed $\varphi_\infty$, which is $4.625 v_\varphi^2$ in an NFW potential. Energy input comparable to $M_{\rm CGM} v_\varphi^2$ can exponentially expand the atmosphere, but energy input that raises $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ to $\varphi_\infty$ drives the atmosphere’s radius to infinity and its pressure normalization to zero.

As $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ approaches $\varphi_\infty$, the assumption of gravitational confinement for $\alpha_{\rm eff} > 3/2$ becomes somewhat artificial, but the associated ExpCGM model may still be useful for quantifying the connection between an atmosphere’s specific energy $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ and its pressure normalization factor $P_0$.

Evolving Potential

The previous section used an NFW profile to represent the potential well of a virialized dark matter halo and found a limiting specific energy $\varphi_\infty \approx 4.6 v_\varphi^2$ for a gravitationally bound atmosphere. However, cosmological halos evolve with time, and the specific energy required to escape an evolving halo can be substantially larger than $4.6 v_\varphi^2$.

Specifying the gravitational potential that binds the matter near the outer radius of a cosmological halo turns out to be a subtle business. Naively, the specific energy required to unbind gas at $R_{\rm halo}$ from the halo’s potential well would seem to be $v_{\rm c}^2 (R_{\rm halo}) = G M_{\rm halo} / R_{\rm halo}$, but that part of the gravitational potential accounts only for the matter currently within $R_{\rm halo}$ and ignores matter at larger radii that has yet to fall into the halo. Therefore, we need to consider the halo’s entire accretion history in order to determine the energy input required for permanent unbinding of atmospheric gas.

Marginally Bound Shell

In the idealized spherical collapse model (see the Accretion page), there is a marginally bound shell containing a mass $M_\infty$ that asymptotically approaches a radius \(R_\infty = \left( \frac {G M_\infty} {H_0^2 \Omega_\Lambda} \right)^{1/3}\) as $t \rightarrow \infty$. All of the shells within the marginally bound shell’s radius are gravitationally bound and ultimately collapse toward $R = 0$. Ideally, the zero point of the overall gravitational potential should result in zero binding energy for the marginally bound shell. However, both $M_\infty$ and $R_\infty$ may be far larger than $M_{\rm halo}$ and $R_{\rm halo}$, because they usually correspond to the mass and radius of the supercluster of galaxies to which the galaxy of interest belongs.

Permanent Escape

More pragmatically, we would like know whether gas that passes outside of $R_{\rm halo}$ early in time, when $M_{\rm halo}$ and $R_{\rm halo}$ are small, still belongs to a galaxy’s atmosphere later on, when both $M_{\rm halo}$ and $R_{\rm halo}$ are considerably larger.

To explore that possibility, we can define $M_0$ to be a halo’s mass at the present time $t_0$. The radius $R_0 (t)$ of the shell containing mass $M_0$ can be computed from the equation of motion for a ballistic shell that reaches its turnaround radius at $t_{\rm ta} = t_0 / 2$. Escaping the gravitational potential of the halo’s eventual mass $M_0$ is easiest at that moment and requires a specific energy $\gtrsim G M_0 / R_0 (t_{\rm ta})$.

According to the spherical collapse model, the halo’s radius at time $t_0$ is $R_{\rm halo} (t_0) \approx R_0 (t_0/2) / 2$. Permanent escape from the evolving halo’s potential therefore requires a specific energy exceeding \(v_0^2 \equiv \frac {G M_0} {2 R_{\rm halo}(t_0)}\) even early in time, when the circular velocity at $R_{\rm halo} (t)$ might be considerably smaller than the value it attains later.

For example, consider a massive galaxy that will eventually become the central galaxy of a large cluster of galaxies. Suppose that the circular velocity of that galaxy is $v_\varphi \sim 400 \, {\rm km \, s^{-1}}$ early in time, while the galaxy is still forming. Later in time that same galaxy will be centered within a galaxy cluster with a circular velocity $v_c \sim 1600 \, {\rm km \, s^{-1}}$ (corresponding to $kT_\varphi \sim 8 \, {\rm keV}$). During that galaxy’s history, the circular velocity at $R_0$ reaches its minimum value $v_0 \sim 1600 \, {\rm km \, s^{-1}} / \sqrt{2}$ at the turnaround time $t_0 / 2$ of the shell containing the cluster’s current mass $M_0$. The value of $v_0^2$ consequently exceeds $8 v_\varphi^2$ while the cluster’s central galaxy is forming. The energy input required to unbind the central galaxy’s atmosphere from the halo’s eventual potential well is therefore an order of magnitude greater than what one would infer from a virialized halo’s potential at early times.

Extended Potential

To account for atmospheric confinement by matter extending beyond the halo, the following extension of the ExpCGM framework includes a model for the extended potential well of that matter. Numerical simulations of cosmological structure formation indicate that the total mass density $\rho_M$ at radii several times $R_{\rm halo}$ declines with an approximate power-law dependence on radius ranging from $r^{-1}$ to $r^{-1.5}$ (e.g., Diemer & Kravtsov 2014, ApJ, 789, 1). Users of the ExpCGM framework may therefore opt to account for the gravitational potential of matter external to the halo using the extended potential \(\varphi_{\rm ext} (r) = 2 \pi G \rho_{\rm ext} R_{\rm halo}^2 \left( \frac {r} {R_{\rm halo}} - 1 \right) \left( 1 - \frac {R_{\rm halo}} {r} \right)\) that results from assuming $\rho_M (r) = \rho_{\rm ext} (r/R_{\rm halo})^{-1}$ outside of $R_{\rm halo}$.

Halo Accretion Parameter

The extended potential’s density normalization factor $\rho_{\rm ext}$ is linked to the halo’s mass accretion rate. Assuming that $\rho_{\rm ext}$ corresponds to matter that is currently accreting onto the halo gives $\rho_{\rm ext} = \dot{M}_{\rm halo} / 4 \pi R_{\rm halo}^2 v_{\rm acc}$ and

$$\varphi_{\rm ext} (r) = \frac {G \dot{M}_{\rm halo}} {v_{\rm acc}} \left( \frac {r} {R_{\rm halo}} - 1 \right) \left( 1 - \frac {R_{\rm halo}} {r} \right)$$

in which $v_{\rm acc}$ is the infall speed of accreting matter.

Notice that the leading factor on the right of the equation breaks up into two factors that are easier to interpret separately:

$$\frac {G \dot{M}_{\rm halo}} {v_{\rm acc}} = \left( \frac {G M_{\rm halo}} {R_{\rm halo}} \right) \left( \frac {R_{\rm halo}} {v_{\rm acc}} \frac {\dot{M}_{\rm halo}} {M_{\rm halo}} \right)$$

The first factor in parentheses is the specific energy required to escape from the radius $R_{\rm halo}$ encompassing a mass $M_{\rm halo}$. The second one is the fraction $f_{\rm acc}$ of a halo’s mass that accretes on a timescale $R_{\rm halo} / v_{\rm acc}$.

In the ExpCGM framework, $f_{\rm acc} \equiv (R_{\rm halo}/v_{\rm acc}) \dot{M}_{\rm halo} / M_{\rm halo}$ is a halo accretion parameter that specifies the normalization of the extended potential as follows: \(\varphi_{\rm ext} (r) = f_{\rm acc} \left( \frac {G M_{\rm halo}} {R_{\rm halo}} \right) \left( \frac {r} {R_{\rm halo}} - 1 \right) \left( 1 - \frac {R_{\rm halo}} {r} \right)\) It can be estimated using the approximation $v_{\rm acc} \approx (G M_{\rm halo} / 2 R_{\rm halo} )^{1/2}$ that comes from spherical collapse, giving

$$f_{\rm acc} \approx 2 \left( \frac {\rho_{\rm cr}} {\rho_{\rm halo}} \right)^{1/2} \frac {\dot{M}_{\rm halo}} {H M_{\rm halo}}$$

where is $H$ is the Hubble expansion parameter, $\rho_{\rm halo}$ is the halo’s mass density, and $\rho_{\rm cr} = 3 H^2 / 8 \pi G$ is the universe’s critical density. Early in cosmic time, while halos are rapidly forming, $f_{\rm acc}$ can be of order unity. However, it becomes closer to $f_{\rm acc} \sim 0.1$ later in time, as structure formation slows down.

Enhanced Confinement

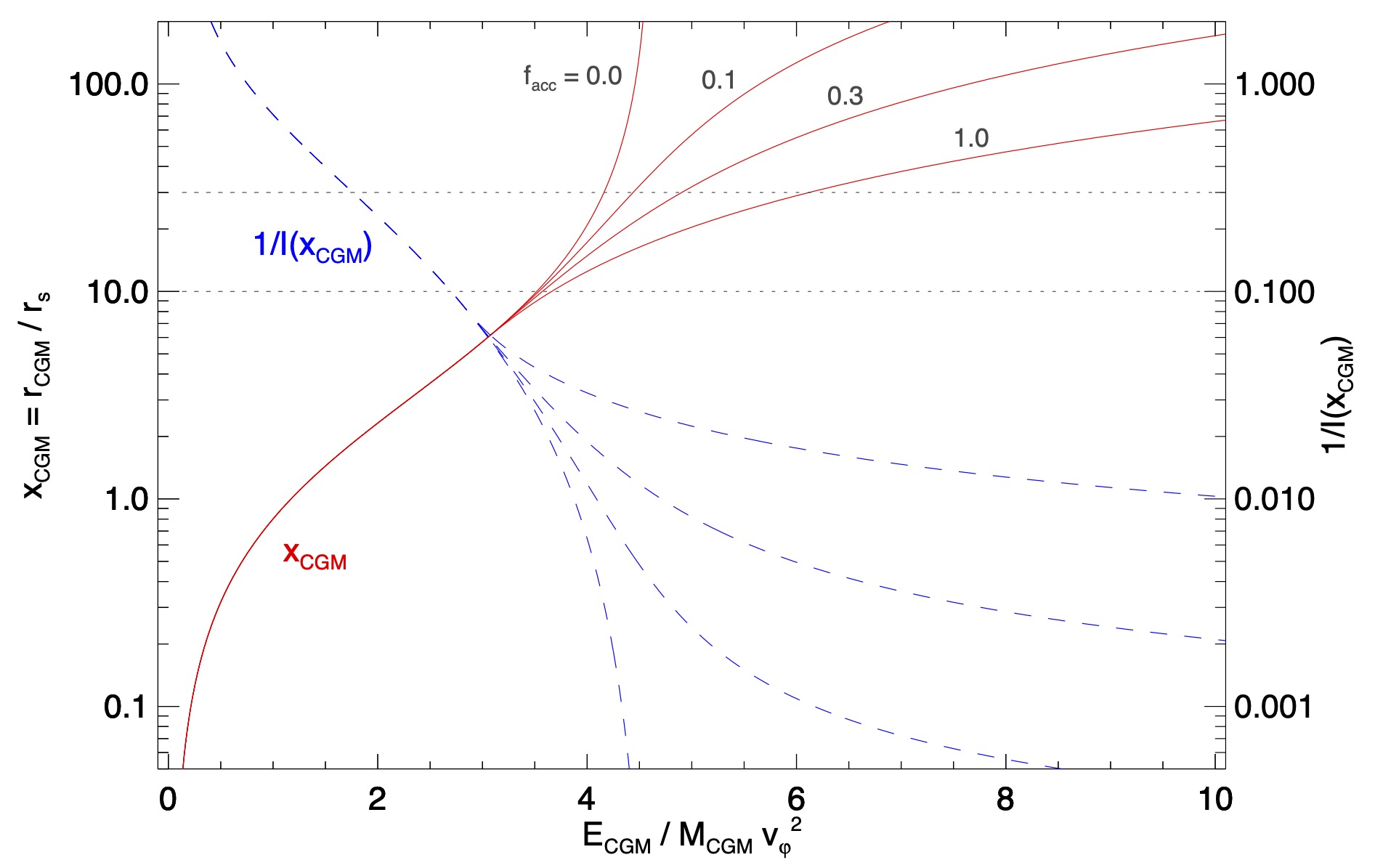

The figure below illustrates how the relationship between an atmosphere’s equilibrium radius $r_{\rm CGM}$ and its mean specific energy $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ depends on $f_{\rm acc}$. It implements an NFW potential well and assumes that thermal pressure follows $P(r) \propto r^{-3/2}$, so that $\alpha = 3/2$. The lines labeled $f_{\rm acc} = 0$ are identical to the corresponding lines in the figure on the Essentials page. Including the extended potential well shifts the atmosphere’s equilibrium states as shown by the lines with $f_{\rm acc} > 0$.

Solid red lines in the figure illustrate how enhanced confinement owing to the extended potential reduces the atmosphere’s equilibrium radius for a given mean specific energy. As $f_{\rm acc}$ increases, those lines extend further to the right, showing that atmospheres with $\varepsilon > 4.6 v_\varphi^2$ can remain bound. Dashed lines in the figure illustrate how the pressure profile normalization $P_0 \propto 1 / I(x_{\rm CGM})$ at $r_0$ declines as $E_{\rm CGM}$ increases.

There are also two horizontal lines. The lower one shows $R_{\rm halo}$ for a halo concentration factor $c_{\rm halo} = R_{\rm halo} / r_{\rm s} = 10$. T upper one shows the approximate stagnation radius ($3 R_{\rm halo} = 30 r_{\rm s}$) beyond which universal expansion is carrying matter away from the halo.

A force-balanced ExpCGM model atmosphere inevitably becomes unrealistic beyond $r \sim 3 R_{\rm halo}$ because the dynamical time there starts to exceed the universe’s age, meaning that the force-balance assumption the model is based on becomes unphysical. Mass shells near $r \sim 3 R_{\rm halo}$ have reached their maximum radii and are just starting to fall back toward the halo. Atmospheric gas pushed beyond $r \sim 3 R_{\rm halo}$ is therefore entering a region where the atmosphere needs to be modeled in a context that accounts for its expansion speed. The factor of 3 can be derived from Kepler’s Third Law, which gives $R_{\rm ta}(t) = 2^{2/3} R_{\rm ta}(t/2) \approx 2^{5/3} R_{\rm halo}(t) \approx 3 R_{\rm halo} (t)$ for the turnaround radius $R_{\rm ta}$ in a spherical collapse model without dark energy.

The extended potential in ExpCGM is formally infinitely deep, because $\varphi_{\rm ext} \rightarrow \infty$ as $r \rightarrow \infty$. Any atmosphere contained within it is therefore gravitationally confined, regardless of its specific energy. However, even an atmosphere that is formally bound becomes extremely diffuse for $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM} \gg G M_{\rm halo} / R_{\rm halo} \sim v_\varphi^2$.