Essentials

This page introduces the most basic building block of ExpCGM: a steady-state galactic atmosphere model. It explains how ExpCGM applies the principles of force balance and atmospheric specific energy to build such a model, then provides a simple example. Descriptions of how ExpCGM accounts for turbulent support and thermalization of atmospheric energy follow the example. A concluding section outlines how the characteristics of steady-state atmosphere models inform ExpCGM methods for evolving those models.

Contents

Force Balance

At the heart of ExpCGM lies an efficient method for determining the steady-state properties of a galactic atmosphere. Each model atmosphere has a total gas mass $M_{\rm CGM}$ and a total energy $E_{\rm CGM}$, and ExpCGM applies a force-balance condition to determine how the atmosphere’s equilbrium radius $r_{\rm CGM}$ depends on $M_{\rm CGM}$ and $E_{\rm CGM}$.

Hydrostatic Equilibrium

The most basic example of a force-balanced atmospheric configuration is hydrostatic equilibrium, described by \(\frac {dP} {dr} = - \rho \frac {d \varphi} {dr}\) where $P$ is thermal pressure, $\rho$ is gas density, and $\varphi$ is a spherically symmetric gravitational potential.

Pressure Shape Function

Direct integration of the hydrostatic equilbrium equation is possible if both the pressure profile’s shape function \(\alpha (r) \equiv - \frac {d \ln P} {d \ln r}\) and the gravitational potential $\varphi(r)$ are known functions of radius. Integrating the shape function leads to a dimensionless pressure profile normalized to unity at a reference radius $r_0$: \(f_P(r) \equiv \exp \left[ - \int_1^{r/r_0} \frac {\alpha (x)} {x} d x \right]\) Providing a pressure normalization $P_0$ at $r_0$ then specifies the atmosphere’s equilibrium pressure profile: \(P(r) = P_0 f_P(r)\)

Many details of an ExpCGM atmosphere model hinge on a user’s choice for the shape function $\alpha(r)$. That choice represents an assumption about the physical processes responsible for maintaining the pressure profile. See the Pressure Profiles page for more detail.

Temperature Profile

A spherical atmosphere supported by thermal pressure in hydrostatic equilibrium has the temperature profile \(T(r) = \frac {2 T_\varphi (r) } {\alpha (r)}\) The function $T_\varphi (r) \equiv \mu m_p v_{\rm c}^2(r) / 2k$ represents a gravitational temperature profile. It comes from solving the hydrostatic equilibrium equation while assuming $P \propto r^{-2}$, a mean mass per atmospheric particle $\mu m_p$, and a gravitational potential with the circular velocity profile $v_{\rm c} (r) = ( r \cdot d \varphi / dr)^{1/2}$. It is normalized so that $T(r) = T_\varphi (r)$ for a hydrostatic atmosphere with $P \propto r^{-2}$ in an isothermal potential well that has constant $v_{\rm c}$. In that special case, both the atmospheric temperature and the ratio of gas density to total mass density are independent of radius.

The astronomical literature often calls something like $T_\varphi$ a virial temperature. However, a galactic atmosphere can have $T \neq T_\varphi$ without violating the virial theorem, because the virial theorem applies to an entire self-gravitating system, not just the gaseous component on its own. Also, a self-gravitating atmosphere with $T \ll T_\varphi$ can satisfy the virial theorem on its own as long as its total kinetic energy provides enough support to balance gravity. That is why ExpCGM calls $T_\varphi$ a gravitational temperature, not a virial temperature.

Density Profile

Given those pressure and temperature profiles, the gas density profile of an equilibrium ExpCGM atmosphere model becomes \(\rho (r) = P_0 \frac {\alpha (r) f_P (r)} {v_{\rm c}^2(r)}\) For example, the gas mass density at the reference radius $r_0$ is simply $\rho_0 = P_0 / (v_c^2 / 2)$ in an equilibrium atmosphere with $\alpha = 2$.

Generalized Force Balance

To represent force-balanced atmospheres partially supported by non-thermal energy, the ExpCGM framework generalizes hydrostatic equilibrium using the force balance equation \(\frac {d} {dr} \frac {P} {f_{\rm th}} = - \rho f_\varphi \frac {d \varphi} {dr}\) The thermalization fraction $f_{\rm th}$ represents the fractional contribution of thermal pressure to the total support opposing gravity. The force modification factor $f_\varphi$ accounts for phenomena (such as rotation) that alter the effective gravitational force pulling the atmosphere inward.

With those generalizations, an ExpCGM atmosphere’s temperature and density profiles become \(T(r) = \frac {2 f_{\rm th} f_\varphi} {\alpha_{\rm eff} (r)} ~T_\varphi (r)~~~~~~,~~~~~~\rho (r) = P_0 \frac {\alpha_{\rm eff} (r) f_P (r)}{f_{\rm th} f_\varphi v_{\rm c}^2(r)}\) Here, the function \(\alpha_{\rm eff} (r) \equiv \alpha(r) + \frac {d \ln f_{\rm th}} {d \ln r}\) is a generalized shape function for atmospheric support, to be used if $f_{\rm th}$ depends on radius. It is also possible for $f_\varphi$ to depend on radius.

While other formulations of atmospheric force balance sometimes express resistance to gravity in terms of a total pressure $P_{\rm tot} = P / f_{\rm th}$, ExpCGM explicitly accounts for the thermal pressure contribution using the $f_{\rm th}$ factor. A model atmosphere’s temperature profile can then be directly inferred from just force balance considerations and the thermalization fraction $f_{\rm th}$. Furthermore, $f_{\rm th}$ can be treated as a dynamical variable, as described below in the Thermalization section.

Specific Energy

A galactic atmosphere of total mass $M_{\rm CGM}$ expands if its total energy $E_{\rm CGM}$ increases, and it contracts if its total energy declines. A galactic atmosphere’s equilibrium radius $r_{\rm CGM}$ therefore depends on its mean specific energy \(\varepsilon_{\rm CGM} = \frac {E_{\rm CGM}} {M_{\rm CGM}}\) Several integrals are needed to determine how $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ depends on $r_{\rm CGM}$ in a force-balanced ExpCGM atmosphere. Inverting that relationship gives the dependence of $r_{\rm CGM}$ on $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$.

Gas Mass

Integrating the gas mass density $\rho(r)$ of an atmosphere in a spherical potential well with maximum circular velocity $v_\varphi \equiv \max (v_{\rm c})$ gives its gas mass profile \(M_{\rm gas} (r) = \frac {4 \pi r_0^3 P_0} {v_\varphi^2} I \left( \frac {r} {r_0} \right) ~~~~~~,~~~~~~I (x) \equiv v_\varphi^2 \int_0^{r/r_0} \frac {\alpha_{\rm eff} (x) f_P (x)} { f_{\rm th} f_\varphi v_{\rm c}^2 (x) } x^2 dx\)

Gravitational Energy

Integrating $\varphi (r) \rho (r)$ gives the atmosphere’s cumulative gravitational energy profile \(E_\varphi (r) = 4 \pi r_0^3 P_0 J_\varphi \left( \frac {r} {r_0} \right) ~~~~~~,~~~~~~J_\varphi (x) \equiv \int_0^{r/r_0} \frac {\alpha_{\rm eff} (x) f_P (x) \varphi(x)} { f_{\rm th} f_\varphi v_{\rm c}^2 (x) } x^2 dx\)

Thermal Energy

Integrating $3 P(r)/2$ gives its cumulative thermal energy profile \(E_{\rm th} (r) = 4 \pi r_0^3 P_0 J_{\rm th} \left( \frac {r} {r_0} \right) ~~~~~~,~~~~~~J_{\rm th} (x) \equiv \frac {3} {2} \int_0^x f_P (x) x^2 dx\)

Non-Thermal Energy

If non-thermal energy components contribute to pressure support, the cumulative non-thermal energy profile is \(E_{\rm nt} (r) = 4 \pi r_0^3 P_0 J_{\rm nt} \left( \frac {r} {r_0} \right) ~~~~~~,~~~~~~J_{\rm nt} (x) \equiv \int_0^x \frac {(1 - f_{\rm th}) f_P (x)} {f_{\rm th} (\gamma_{\rm nt} - 1)} x^2 dx\) The factor $\gamma_{\rm nt} - 1$ in the integral’s denominator is the local ratio of non-thermal pressure support to non-thermal energy density, and it can be different from 2/3.

Total Specific Energy

To obtain a galactic atmosphere’s mean specific energy, the ExpCGM framework adds up the energy integrals to make the function \(F(x) = \frac { J_\varphi (x) + J_{\rm th}(x) + J_{\rm nt}(x)} {I(x)}\) It is defined so that the equation \(\varepsilon_{\rm CGM} = v_\varphi^2 F \left( \frac {r_{\rm CGM}} {r_0} \right)\) relates an atmosphere’s mean specific energy $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ to its equilibrium radius $r_{\rm CGM}$.

Equilibrium Radius

Inverting $F(x)$ then gives the atmosphere’s equilibrium radius $r_{\rm CGM} = x_{\rm CGM} r_0$ as a function of $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM} / v_\varphi^2$: \(r_{\rm CGM} = r_0 F^{-1} \left( \frac {\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}} {v_\varphi^2} \right)\)

Pressure Normalization

Once an ExpCGM atmosphere’s equilibrium radius has been determined, the relation \(P_0 = \frac {M_{\rm CGM} v_\varphi^2} {4 \pi r_0^3} \frac {1} {I(r_{\rm CGM}/r_0)}\) gives the pressure profile’s normalization at $r_0$.

These relationships between $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$, $r_{\rm CGM}$, and $P_0$ are the cornerstones of all ExpCGM atmosphere models. They depend primarily on a user’s choices for $\varphi(r)$ and $\alpha(r)$ and determine how the resulting atmosphere expands or contracts as its total mass and energy change. They may also depend on a user’s choices for $f_{\rm th}(r)$ and $f_\varphi(r)$.

A Simple Example

The following example illustrates how solutions for steady-state atmospheric structure emerge from the ExpCGM framework.

Power-Law Pressure Profile

First, assume that the atmosphere has a power-law pressure profile (constant $\alpha$), that the atmosphere’s support energy is purely thermal ($f_{\rm th} =1$), and that there are no radial forces other than gravity ($f_\varphi =1$). In that case, an ExpCGM atmosphere’s steady-state pressure, temperature, and density profiles become \(P(r) = P_0 \left( \frac {r} {r_0} \right)^{-\alpha}~~~~,~~~~T(r) = \frac {2 T_\varphi (r)} {\alpha} ~~~~,~~~~\rho (r) = \frac {\alpha P_0} {v_{\rm c}^2(r)} \left( \frac {r} {r_0} \right)^{-\alpha}\)

NFW Potential Well

Next, consider confinement by an Navarro-Frenk-White (NFW) gravitational potential with a zero point at $r=0$. We can express that potential as \(\varphi_{\rm NFW} (x) = A_{\rm NFW} v_\varphi^2 \left[ 1 - \frac {\ln (1 + x)} {x} \right]\) in which $x = r / r_{\rm s}$ represents how $r$ compares with the potential’s scale radius $r_{\rm s}$. Choosing $A_{\rm NFW} = 4.625$ makes the parameter $v_\varphi^2$ equal to the maximum value of the NFW circular velocity profile \(v_{\rm c}^2 (x) = A_{\rm NFW} v_\varphi^2 \left[ \frac {\ln (1 + x)} {x} - \frac {1} {1 + x} \right]\) For convenience, we will choose $r_0$ to be identical to $r_{\rm s}$ in this example, so that $P_0$ is the thermal pressure at $r_{\rm s}$.

Energy and Mass Integrals

With those choices, the integrals needed for determining the atmosphere’s equilibrium radius simplify. The integral giving the dimensionless gas mass profile simplifies to \(I(x) = \frac {\alpha} {A_{\rm NFW}} \int_0^x \left[ \frac {x} {\ln (1+x) - x / (1 + x) } \right] x^{2 - \alpha} dx\) The integral giving the cumulative gravitational energy profile simplifies to

\(J_\varphi(x) = \alpha \int_0^x \left[ \frac {x - \ln (1 + x)} {\ln (1+x) - x / (1 + x)} \right] x^{2 - \alpha} dx\) The cumulative thermal energy profile becomes an algebraic function: \(J_{\rm th}(x) = \frac {3 x^{3-\alpha}} {6 - 2\alpha}\) There is no need to compute $J_{\rm nt} (x)$ because all of the support energy is thermal.

Energy and Expansion

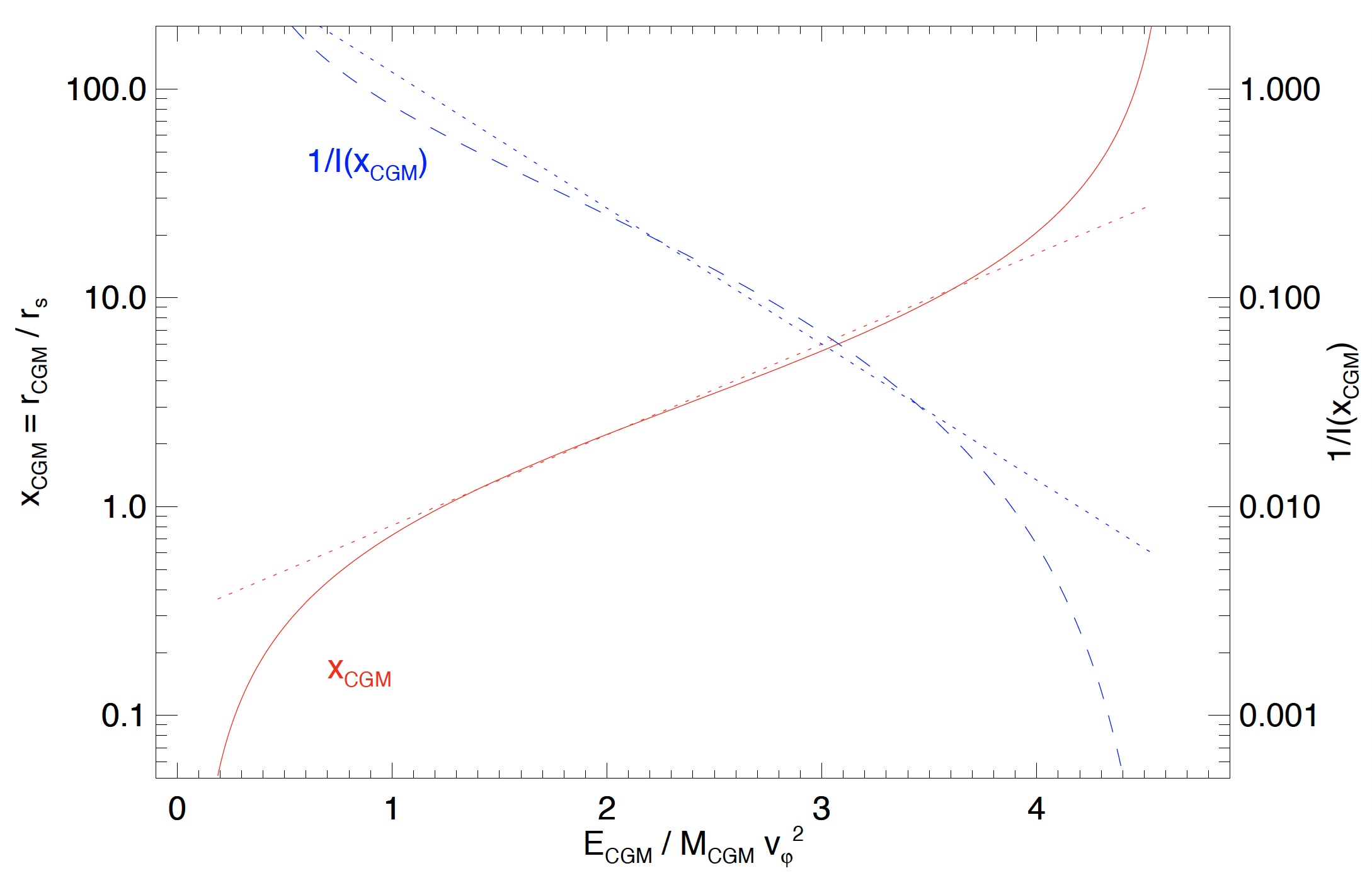

The figure below shows the relationship between mean specific energy and atmospheric radius that follows from these integrals. A solid red line represents how the atmosphere’s equilibrium radius $r_{\rm CGM} = x_{\rm CGM} r_{\rm s}$ depends on its mean specific energy $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM} = E_{\rm CGM} / M_{\rm CGM}$ for a case with $\alpha = 3/2$. The equilibrium radius starts at zero for $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM} = 0$ and rises through $r_{\rm CGM} \approx 6 r_{\rm s}$ at $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM} \approx 3 v_\varphi^2$. The atmosphere’s radius then formally approaches infinity as $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ approaches $A_{\rm NFW} v_\varphi^2$ because atmospheric gas with specific energy exceeding $A_{\rm NFW} v_\varphi^2$ is unbound. A dashed blue line shows how the normalization $P_0 \propto 1/ I(x_{\rm CGM})$ of the atmosphere’s pressure profile declines as $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ rises and the atmosphere expands.

Dotted lines in the figure illustrate relationships that are exponentially sensitive to the scaled specific energy $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM} / v_\varphi^2$. They are similar to the solid and dashed lines within the range $v_\varphi^2 \lesssim \varepsilon_{\rm CGM} \lesssim 4 v_\varphi^2$. However, the functions describing the atmosphere’s equilibrium radius and pressure normalization become even more sensitive than those exponential relationships as $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ surpasses $4 v_\varphi^2$. Consequently, feedback mechanisms capable of boosting the atmosphere’s mean specific energy above $4 v_\varphi^2$ drastically reduce its density and radiative cooling rate.

The relationship between $r_{\rm CGM}$ and $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ would be purely exponential for an atmosphere with constant $\alpha$ in a gravitational potential with constant $v_{\rm c}$. That is why the relationships in the figure are nearly exponential in the portion of an NFW potential well in which $v_{\rm c}$ is nearly constant.

Turbulent Support

The ExpCGM framework was intentionally designed to model galactic atmospheres jointly supported by both thermal energy and non-thermal gas motions usually called “turbulence” even though they do not necessarily arise from a classic Kolmogorov cascade of eddies. For simplicity, ExpCGM treats those gas motions as isotropic, with a one-dimensional velocity dispersion $\sigma_{\rm 1D}$.

The specific energy of a force-balanced atmosphere at radius $r$ is then

$$\varepsilon(r) ~=~ \varphi(r) + \frac {3} {2} \left( \frac {P} {\rho} + \sigma_{\rm 1D}^2 \right) ~=~ \varphi(r) + \frac {3 f_\varphi v_{\rm c}^2} {2 \alpha_{\rm eff}}$$

and its thermalization fraction is \(f_{\rm th} = \frac {P} {P + \rho \sigma_{\rm 1D}^2}\) Notice that the sum of thermal and turbulent energy density depends only on $f_\varphi v_{\rm c}^2$ and $\alpha_{\rm eff}$, and does not depend on $f_{\rm th}$.

Thermalization

Dissipation of turbulent support energy does not change the radius of a force-balanced galactic atmosphere because the total support jointly provided by turbulent and thermal energy is independent of $f_{\rm th}$. Turbulent dissipation simply increases $f_{\rm th}$ without altering a force-balanced atmosphere’s overall structure. ExpCGM therefore tracks thermalization of turbulence as dissipation proceeds using a differential equation for $f_{\rm th}$ appropriate for an atmosphere jointly supported by turbulence and thermal energy.

Energy Injection

User-specified models provide the total energy injection rate $\dot{E}_{\rm inj}$ at which cosmological accretion and galactic feedback add non-gravitational energy to a galaxy’s atmosphere. That energy input branches into a fraction $f_{\rm inj,th}$ going directly into heat and a complementary fraction $1 - f_{\rm inj,th}$ initially going into turbulence. An ExpCGM user can specify the value of the parameter $f_{\rm inj,th}$. That parameter can also depend on the relative contributions of cosmological accretion and feedback to $\dot{E}_{\rm inj}$.

Dissipation Timescale

In ExpCGM, turbulence dissipates into heat on a timescale $t_{\rm diss} = \lambda_{\rm diss} / \sigma_{\rm 1D}$, in which $\lambda_{\rm diss}$ is a length scale characterizing the driving of turbulence. An ExpCGM user can specify the value of $\lambda_{\rm diss}$ relating $\sigma_{\rm 1D}$ to $t_{\rm diss}$.

Evolution of Thermalization

Energy injection, dissipation, and radiative cooling all affect the fraction $f_{\rm th}$ of support energy in thermal form.

-

Energy injection changes the atmosphere’s total amount of support energy $E_{\rm th} / f_{\rm th}$ on the timescale $t_{\rm inj} \equiv E_{\rm th} / f_{\rm th} \dot{E}_{\rm inj}$.

-

Dissipation converts turbulence into thermal energy at the rate $\dot{E}_{\rm diss} = (1 - f_{\rm th}) E_{\rm th} / f_{\rm th} t_{\rm diss}$.

-

Radiative cooling happens on a timescale $t_{\rm cool} \equiv E_{\rm th} / \dot{E}_{\rm rad}$, where $\dot{E}_{\rm rad}$ is a radiative loss rate computed from the atmosphere model.

The rate at which $f_{\rm th}$ changes in ExpCGM is derived from the overall rate of change in total atmospheric support energy

$$\frac {d} {dt} \frac {E_{\rm th}} {f_{\rm th}} = \dot{E}_{\rm inj} - \dot{E}_{\rm rad} - \dot{E}_{\varphi,{\rm exp}}$$

and the rate of change in thermal support energy

$$\dot{E}_{\rm th} = \dot{E}_{\rm diss} - \dot{E}_{\rm rad} - f_{\rm th} \dot{E}_{\varphi,{\rm exp}} + f_{\rm inj,th} \dot{E}_{\rm inj}$$

In both of these equations, $\dot{E}_{\varphi,{\rm exp}}$ is the conversion rate of atmospheric support energy into gravitational energy. The value of $\dot{E}_{\varphi,{\rm exp}}$ is positive in an expanding atmosphere and negative in a contracting atmosphere.

The equation for $\dot{E}_{\rm th}$ assumes that expansion and contraction are slow enough to have no effect on $f_{\rm th}$. This assumption is based on both thermal energy and turbulent energy having the same ratio of energy density to pressure, which gives them the same polytropic equation of state. However, an expanding or contracting atmosphere that is rapidly settling into a force-balanced state may be converting the kinetic energy of bulk flow into a combination of turbulent and thermal energy with a ratio different from $(1 - f_{\rm th}) / f_{\rm th}$. In principle, ExpCGM users can account for such differences through adjustments to the branching ratio $f_{\rm inj,th}$ for thermal energy injection.

Combining the ExpCGM equations for the rates of change in $E_{\rm th} / f_{\rm th}$ and $E_{\rm th}$ leads to

$$\frac {E_{\rm th}} {f_{\rm th}} \frac {d f_{\rm th}} {dt} = \dot{E}_{\rm diss} - \left( 1 - f_{\rm th} \right) \dot{E}_{\rm rad} + \left( f_{\rm inj,th} - f_{\rm th} \right) \dot{E}_{\rm inj}$$

The time derivative of $f_{\rm th}$ can therefore be expressed as

$$\frac {d f_{\rm th}} {dt} = \frac {1 - f_{\rm th}} {t_{\rm diss}} - \frac {(1 - f_{\rm th}) f_{\rm th}} {t_{\rm cool}} + \frac {(f_{\rm inj,th} - f_{\rm th})} {t_{\rm inj}}$$

which explicitly connects changes in $f_{\rm th}$ to the three timescales for energy exchange.

This equation for how atmospheric thermalization changes with time does not depend on the volume of gas being considered. It can be applied to a global value of $f_{\rm th}$ characterizing the entire atmosphere. It can also be applied to individual shells of atmospheric gas with differing values of $t_{\rm diss}$, $t_{\rm cool}$, $t_{\rm inj}$, and $f_{\rm inj,th}$.

Atmospheric Evolution

An ExpCGM atmosphere model evolves as $E_{\rm CGM}$ and $M_{\rm CGM}$ evolve. At each moment in time, ExpCGM assumes that the atmosphere is in a force-balanced configuration that depends on $E_{\rm CGM}$, $M_{\rm CGM}$, $v_{\rm c}(r)$, and $\alpha_{\rm eff}(r)$, as described above. Whether or not the atmosphere is expanding or contracting depends on how $\varepsilon_{\rm CGM}$ is changing and therefore hinges on how energy input compares with radiative cooling.

To determine the atmosphere’s heating and cooling rates, ExpCGM uses a steady-state atmosphere model to calculate the radiative cooling rate $\dot{E}_{\rm rad}$ at which energy leaves the atmosphere and the gas supply rate $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ at which gas flows from the CGM into a halo’s central galaxy. That inflow feeds a buildup of galactic gas leading to star formation, supernova explosions, and galactic outflows that return gas and energy to the atmosphere. When averaged over sufficiently long time periods, the rate of energy input from stars is proportional to the time-averaged value of $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$.

Radiative Cooling

Radiative losses happen when two-body collisions produce photons that are not reabsorbed. A galactic atmosphere’s radiative cooling rate per unit volume is therefore proportional to $\rho^2$ and a temperature-dependent cooling function accounting for the atmosphere’s ionization state, the relative speeds of colliding particles, and the cross-sections for excitation of photon emission.

In ExpCGM, the cooling function $\Lambda_\rho (T)$ is defined so that the radiative energy loss rate per unit volume is $\rho^2 \Lambda_\rho$ and the specific cooling rate is $\rho \Lambda_\rho$. Integration over shells of radius $r$ then gives the atmosphere’s total radiative cooling rate

$$\dot{E}_{\rm rad} = \int_0^{r_{\rm CGM}} \langle \rho \Lambda_\rho \rangle ~4 \pi r^2 \bar{\rho} ~dr$$

in which $\langle \rho \Lambda_\rho \rangle$ represents the mass-averaged value of the specific cooling rate within a gas shell of mean density \(\bar{\rho}(r) = \frac {P(r)} {f_{\rm th}} \frac {\alpha_{\rm eff}(r)} {f_\varphi v_{\rm c}^2 (r)}\) This approach enables ExpCGM to account for inhomogeneities that can make the cooling rate of a multiphase gas shell dramatically different from the cooling rate of a homogeneous gas shell with $\rho = \bar{\rho}$. (See the Cooling and Multiphase Gas pages for more detail.)

The cooling function $\Lambda_\rho (T)$ used here is related to the more familiar cooling function $\Lambda (T)$ via the expression $\rho^2 \Lambda_\rho = n_e n_i \Lambda$, in which $n_e$ is the electron density and $n_i$ is the ion density. Using $\Lambda_\rho (T)$ instead of $\Lambda (T)$ helps to make the notation representing the specific cooling rate more compact and intuitive.

Galactic Gas Supply

The gas supply rate $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ is a customizable feature of ExpCGM. In many cases, the simplest physically motivated approach is to assume steady-state inflow at an inflow speed $v_{\rm in}$ that satisfies \(v_{\rm in} \frac {\partial \varepsilon} {\partial r} = \langle \rho \Lambda_\rho \rangle\) Radiative cooling then offsets the internal energy gains coming from gravitational compression as atmospheric gas flows inward. The corresponding gas supply rate is

$$\dot{M}_{\rm in} = 4 \pi r^2 \bar{\rho} v_{\rm in}$$

evaluated at a user-specified radius $r_{\rm gal}$ marking the boundary between galactic gas and circumgalactic gas.

A useful estimate, applicable when $v_{\rm c}^2$ and $\alpha_{\rm eff}$ are nearly independent of $r$, comes from assuming \(\frac {\partial \varepsilon} {\partial r} = \frac {d \varphi} {dr} = \frac {v_{\rm c}^2} {r}\) The inflow speed and gas supply rate are then

$$v_{\rm in} = \frac {r \langle \rho \Lambda_\rho \rangle} {v_{\rm c}^2} ~~~~~,~~~~~ \dot{M}_{\rm in} = \frac {4 \pi r^3 \bar{\rho} \langle \rho \Lambda_\rho \rangle} {v_{\rm c}^2}$$

as given by the force-balanced atmosphere model at $r_{\rm gal}$.

According to this approach, atmospheric heating does not directly affect the gas supply rate to the central galaxy. Instead, atmospheric heating indirectly reduces $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ by expanding a galaxy’s atmosphere, thereby lowering both the mean density $\bar{\rho}$ and specific cooling rate $\langle \rho \Lambda_\rho \rangle$ of atmospheric gas at $r_{\rm gal}$. Conceptually, this treatment of atmospheric heating corresponds to an energy supply that flows outward along directions different from the ones along which inflow is occuring, without significantly inhibiting the inflow.

Cooling Time

Rewriting the expressions for $v_{\rm in}$ and $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ in terms of cooling time helps to make them more intuitive. In a force-balanced ExpCGM atmosphere model, the cooling time of a particular gas shell is

$$t_{\rm cool} ~=~ \frac {3 P} {2 \bar{\rho} \langle \rho \Lambda_\rho \rangle} ~=~ \left( \frac {3 f_\varphi} {2 \alpha_{\rm eff}} \right) \frac {f_{\rm th} v_{\rm c}^2} {\langle \rho \Lambda_\rho \rangle}$$

The approximations for inflow speed and gas supply can therefore be expressed as

$$v_{\rm in} = \left( \frac {3 f_\varphi} {2 \alpha_{\rm eff}} \right) \frac {r f_{\rm th}} {t_{\rm cool}} ~~~~~,~~~~~ \dot{M}_{\rm in} = \left( \frac {3 f_\varphi} {2 \alpha_{\rm eff}} \right) \frac {4 \pi r^3 \bar{\rho} f_{\rm th}} {t_{\rm cool}}$$

In other words, atmospheric gas flows inward on a timescale comparable to $t_{\rm cool} / f_{\rm th}$, because the model-dependent quantity $3 f_\varphi / 2 \alpha_{\rm eff}$ is generally close to unity.

Radiative and Dissipative Limits

This approach has two characteristic limiting cases:

-

Radiative Inflow $(t_{\rm diss} \ll t_{\rm cool} \ll t_{\rm inj})$. When dissipation is rapid compared to radiative cooling, turbulence quickly converts into heat, ensuring that $f_{\rm th} \approx 1$. The central galaxy’s gas supply therefore flows inward on a timescale similar to $t_{\rm cool}$. If the atmosphere remains sufficiently homogeneous and nearly isothermal, then $t_{\rm cool}(r)$ is proportional to $1/\bar{\rho}(r)$. The value of $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ is then independent of radius for $\bar{\rho} \propto r^{-3/2}$, corresponding to $\alpha = 3/2$, which is the classic power-law profile of a steady cooling flow.

-

Dissipative Inflow $(t_{\rm cool} \ll t_{\rm diss} \ll t_{\rm inj})$. When radiative cooling is rapid compared to dissipation, an atmosphere’s thermal support is quickly lost. Turbulence then needs to supply most of the atmosphere’s support. According to the equation for $d f_{\rm th} / dt$, the atmosphere’s thermal support fraction converges toward $f_{\rm th} \approx t_{\rm cool} / t_{\rm diss}$, and so the central galaxy’s gas supply flows inward on a timescale similar to $t_{\rm diss}$. Furthermore, the density profile that makes $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ independent of $r$ for $t_{\rm diss} \propto r$ is $\bar{\rho} \propto r^{-2}$. That corresponds to $\alpha_{\rm eff} = 2$ and is the classic power-law profile of a steady dissipative inflow proceeding inward at constant speed.

Evolving ExpCGM atmosphere models can smoothly transition from one limit to the other, and can also remain balanced between those limiting cases, because of how ExpCGM tracks changes in $f_{\rm th}$ over time.

The gas supply rate $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ obtained with this approach depends somewhat on a user’s choice of $r_{\rm gal}$, except for the two special cases mentioned above: $\alpha \approx 3/2$ for a steady radiative inflow and $\alpha_{\rm eff} \approx 2$ for a steady dissipative inflow. However, the feedback fueled by $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ in an evolving ExpCGM model adjusts the atmosphere’s pressure normalization ($P_0$) so that $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ approaches a steady-state value that is nearly independent of $r_{\rm gal}$.

Freefall-Limited Inflow

The assumptions that ExpCGM is built on break down when both $t_{\rm cool}$ and $t_{\rm diss}$ are short enough to make $r f_{\rm th} / t_{\rm cool}$ faster than $v_{\rm c}$. In that limit, both thermal and non-thermal support fail to keep the atmosphere close to force balance. Halo gas then falls nearly freely into the central galaxy, unless rotation can support it.

To prevent unphysically large gas supply rates, ExpCGM limits $\dot{M}_{\rm in}$ to be no greater than

$$\dot{M}_{\rm in,max} = 4 \pi r_{\rm gal}^2 \bar{\rho}(r_{\rm gal}) v_{\rm c} (r_{\rm gal})$$

With this restriction, circumgalactic gas cannot fall into a halo’s central galaxy faster than gravity can accelerate it.

Galactic Feedback

An ExpCGM galactic atmosphere recovers at least some of the support energy it has lost to radiation when energy released from the central galaxy couples with the CGM. The time-averaged rate of feedback energy input depends on how much star formation results from the central galaxy’s gas supply. It may also depend on how much of the galaxy’s gas accretes onto its central black hole.

A major goal of ExpCGM is to emulate how those interactions between galaxies and their atmospheres become a self-regulating feedback loop. The Regulation page explains how ExpCGM does that.

Cosmic Accretion

Cosmological structure formation also supplies both mass and energy to a galaxy’s atmosphere. The rate at which it adds energy is

$$\dot{E}_{\rm acc} = \left[ \varphi(R_{\rm halo}) + \frac {v_{\rm c}^2} {2} (R_{\rm halo}) \right] \dot{M}_{\rm acc}$$

where $R_{\rm halo}$ is a user-defined radius for the galaxy’s dark matter halo, and $\dot{M}_{\rm acc}$ is the rate at which cosmological accretion adds gas mass accretion rate. Usually, $\dot{M}_{\rm acc}$ is directly proportional to the halo’s total cosmological mass accretion rate $\dot{M}_{\rm halo}$.

Cosmological structure formation can also change both the maximum circular velocity ($v_\varphi$) and scale radius ($r_{\rm s}$) of the gravitational potential, thereby changing the gravitational potential energy of gas that has already accreted at the rate

$$\dot{E}_{\varphi,{\rm cos}} = 4 \pi \int_0^{r_{\rm CGM}} \dot{\varphi} (r) \rho(r) r^2 dr$$

Notice that this rate depends on both the rate $\dot{\varphi} (r)$ at which the gravitational potential changes and the atmosphere’s mass density profile $\rho(r)$. The Accretion page provides more detail.

Total Energy Input

The total input rate for atmospheric energy is therefore

$$\dot{E}_{\rm inj} = \dot{E}_{\rm fb} + \dot{E}_{\rm acc} + \dot{E}_{\varphi,{\rm cos}}$$

Supplementary models can be implemented to determine how energy input changes $f_{\rm th}(r)$ and perhaps also $\alpha (r)$. The Pressure Profiles page discusses various physically motivated options for the shape function $\alpha (r)$ and the gravitational potential correction factor $f_\varphi (r)$. (A future Rotation page, not yet developed, will elaborate on the relationship between $f_\varphi (r)$ and atmospheric rotation.)

The ExpCGM framework splits the total rate of change in atmospheric gravitational energy $E_\varphi$ into a component $\dot{E}_{\varphi,{\rm cos}}$ corresponding to the cosmological evolution of $\varphi(r)$ and a component $\dot{E}_{\varphi,{\rm exp}}$ corresponding to the hydrodynamic evolution of $r_{\rm CGM}$. Only the cosmological component changes the atmosphere’s total energy, because $\dot{E}_{\varphi,{\rm exp}}$ represents internal conversion of support energy into gravitational energy and vice versa.